First, let’s look at the evidence as it relates to the Union to determine whether there was any adherence to a guiding military theory, Jominian or otherwise. In With a Sword in One Hand and Jomini in the Other, Carol Reardon casts doubts on whether Jomini’s ideas had any significant influence over the decisions of Lincoln’s military leaders. When rebellion appeared inevitable, she traces a hypothetical search of Jomini’s types of wars by Lincoln’s first general-in-chief. The conflict before General Winfield Scott did not neatly fall into any of Jomini’s definitions. As Reardon observes, Jomini does briefly address “civil wars,” in which he states that a government “may find it necessary to use force against its own subjects in order to crush out factions which would weaken the authority of the throne and the national strength.” But even had Scott, or McClellan, or even Lincoln looked to Jomini, they would have found his advice in such matters to be nearly nonexistent.[1] In addition, the United States military did not possess the kind of general staff that Jomini – and much of Europe – prescribed.[2] Once the Union army was finally set in motion, the public and even her soldiers were often unable to discern any strategy over the subsequent years. Perhaps telling of the general opaqueness of Northern strategy, the 22 June 1864 edition of The Soldier’s Journal printed an explanation of a commonly heard tactic often confusingly used in strategic discussions: “The rank and file have a pretty good appreciation of the strategy of the campaign. They understand that it has been a series of splendid flank movements, and flanking ‘became the current Joke with which to account for everything from a night march to the capture of a sheep or pig. A poor fellow, terribly wounded, yesterday, said he saw the shell coming, ‘but hadn’t time to flank it.'”[3]

The greatest indication of whether the Union followed Jominian, or any other, theory should come from an analysis of the actual strategy followed throughout the war. If Davis Donald’s assertion is valid, then something of Jomini’s ideas should be reflected in the Union’s operations. What guided Lincoln and his line of Generals to act as they did between 1861 and 1865? Did their operations conform to an overall strategy that reflected a coherent military theory?

From the outset, President Lincoln was sensitive to the fragile neutrality declared by the Border States – Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri. This political situation complicated war planning from the beginning. In Maryland, riots broke out on April 18, 1861, as pro-secessionists protested the movement of troops into Washington D.C.[4] In response, President Lincoln and General Winfield Scott, despite their concerns of a potential uprising in the capital or an invasion from the South, ordered that troops should march around Baltimore instead of traveling through the city.[5] In Kentucky, Lincoln initially hesitated to deploy Federal forces because of the fear such action would stoke sympathies with the South. In July 1861, he drafted a letter to the Inspector General of the Kentucky State Guard, assuring him that he had no intention of sending troops to his home state at that time.[6] It wasn’t until after state elections in August, which demonstrated that Kentucky retained significant Union support, that Lincoln authorized a force be sent to the state, despite the objections from the governor.[7]

This sensitive environment had a direct effect on the North’s ability to coordinate any kind of cohesive strategy that emphasized the quick massing of forces to concentrate on the enemy’s “fractions.” Lincoln understood this, and pressed his generals to find a way to be aggressive while minding the political realities the Union faced. With a clear superiority of men and materiel, the Union soon determined to use its navy to gain control of the Mississippi River, which would split the Confederacy, the Atlantic coastline of the Eastern states, and New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico. Firmly encircled, Lincoln thought to push all around the South’s periphery until the Southern army was exhausted. Eventually dubbed “Scott’s Anaconda Plan” (in spite of the fact that General Scott actually opposed the idea), this strategy required patience, and flew in the face of the popular understanding of Jominian and European warfare.[8]

Even as this plan took shape, pressure grew in the North to take action, particularly with an enemy force literally in sight of Washington. Yet due to the sensitive situation in Maryland, it took three months after the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861 to put together a 35,000-strong army to march south to try and seize the strategic Manassas Junction near Bull Run. Ideally, the Union force would have been much larger, but pressure from a public hungry for action eventually forced Scott’s hand. In addition, President Lincoln’s concern over the Border States and a potential attack on the capital sapped manpower from the army to be led by General Irvin McDowell (West Point Class of 1938).[9]

General McDowell proposed an approach to Bull Run that circled around the entrenched Confederate forces, which targeted the rail system that connected Manassas with Richmond. His intent was to threaten the Confederates, led by P.G.T. Beauregard, with isolation from Richmond.[10] The plan was complicated, but McDowell’s peers and superiors approved it. In Jominian terms, the decisive points had been determined within the theater of war. McDowell’s base of operations could be said to have stretched from Washington DC, or possibly immediately across the river at Alexandria, which the Union secured upon departing for Manassas.

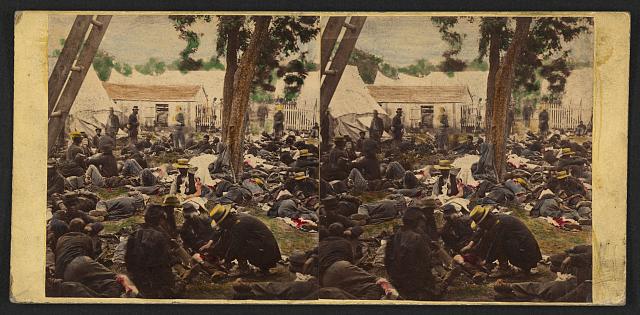

Despite competent planning and a respectable initial execution, McDowell’s operations eventually broke down under the weight of the fog and friction of war. The Union general faced the unexpected combination of Beauregard’s and Joe Johnston’s forces, and so his ability to ascertain decisive points suffered greatly. Instead of flanking the main Confederate force and striking a fraction of the enemy with the mass of his own, his forces wound up engaging a concentrated foe. As the bloody conflict shifted to Henry Hill, the Union forces started to break down. The commander of a Union light artillery battery described how after almost a full day of combat, a mass of several thousand men without distinguishing colors rapidly closed in. At first, the troops were thought to be Union soldiers. Suddenly, the battery found itself under fire. “We had been surprised, and the enemy was close upon us in large numbers.”[11] By the early evening, Union forces were forced to fall back.

McDowell’s forces retreated back to Washington in a disorganized mess. Certainly, the Union general had to deal with challenges that Jomini and other famed European theorists famously ignored, such as the quality of troops. In the rush “on to Richmond” McDowell had been outfitted with raw recruits and had little time to train them. What might he had done with a more seasoned force is a matter of conjecture. The Federal action at Bull Run does arguably demonstrate the exercise of Jominian theory at the operational level. In addition, since Winfield Scott anticipated a victory that would open the way for a march on the Confederate capital at Richmond, the operation was planned to serve a strategic purpose that is arguably a reflection of Jominian theory. However, the route at Bull Run stumped the leadership in Washington, and whether by design or accident, the following years saw little in the way of a cohesive strategy.

Lincoln now had to contend with an emboldened rebellion, and not just in the South. Concerns arose that secessionists in the Border States might rally to the victorious Confederate cause. “We have just heard of the reverses our arms have sustained in Virginia and we anticipate a large increase of courage if not numbers in the rebels,” wrote an officer of the Missouri volunteer forces just days after Bull Run. ”North Missouri is throroughly [sic] indoctrinated with sublimated political themes at war with all government and now while the popular pride is aroused, may be easily set in flames.”[12] Lincoln had to move, but in a way that brought victory as quickly as possible without eroding the loyalty of the Border States.

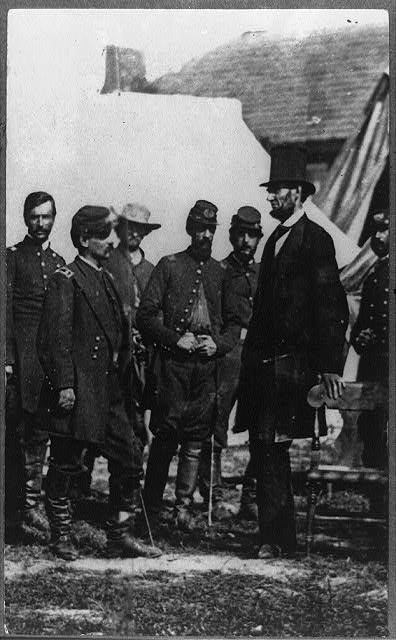

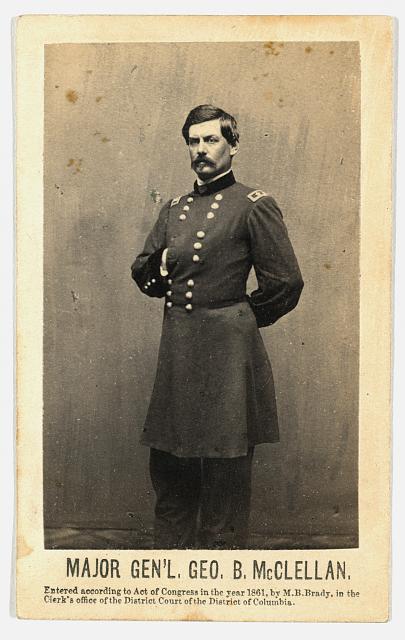

General George McClellan stepped into the role of general-in-chief after General Scott retired on November 1, 1861. His

first plan of action was to attempt to concentrate forces for an attack on Virginia. In order to successfully execute Lincoln’s objectives, he needed the entire military apparatus to be unified into a single whole, and not operated piecemeal as even Lincoln recognized the case to be at the time.[13] This concept can certainly be traced to Jomini. But McClellan’s plans ran into the political snares Lincoln had been struggling with since the start of the war. The forces McClellan intended to draw to Washington were stationed in and around the Border States. Pro-Union politicians complained that moving these forces exposed their states to threats, and eventually McClellan had to alter his plans. Interestingly, this consisted of pressuring the South from all directions, which sounds quite a bit like “Scott’s Anaconda Plan.”[14] Against his better judgment, it seemed, McClellan was forces to operate outside of a Jominian paradigm.

General McClellan’s most notorious action was his conduct of the Peninsula Campaign, wherein he attempted a feint of sorts against Richmond. He planned to attack the Confederate capital by an amphibious operation rather than approach overland. When McClellan finally began his movement in April 2012, his actions displayed little evidence that he incorporated any military theory at all, much less any Jominian influence. McClellan’s penchant for delay and exaggeration were both on display. After arriving at Yorktown on 3 April, Union forces seized positions outside the town. By 5 April they traded artillery fire with the Confederates. But rather than continue his advance, the general opted to fortify his position by building earthworks. This move surprised Confederate Major General J. Bankhead Magruder, who had expected the Northerners to press forward with their superior numbers.[15] The delay allowed for Confederate reinforcements to arrive, which fueled McClellan’s belief that he was outnumbered, although even by 12 April he continued to maintain a 3 to 1 advantage over the rebels. Blaming poor weather and a lack of wagons, his further delay continued to cost him, as by 17 April General Joseph Johnston arrived, bringing the defender’s numbers to 53,000 (compared to the roughly 100,000 strong Union Army). [16]

On 3 May, exactly one month after arriving at Yorktown, Confederate forces fell back toward Richmond rather than face bombardment from McClellan’s siege. McClellan ordered a pursuit, but it was slow. Although his approach and the arrival of Union gunboats outside of Richmond caused a partial evacuation of the city, the Federal naval forces were forced to turn away by the prepared Confederate defenses.[17] From 25 June – 1 July, 1862, Union and Confederate forces slugged it out in what became known as the Seven Days. Within days of what was to be the final great battle of the Civil War, McClellan turned his forces back toward the James River and retreated.

The failure of the Peninsula Campaign demonstrated that the Union’s one time general-in-chief (he had been removed from that post only four months after stepping into it), who was hailed early on in the conflict as a master of the art of war, was unable to put anything resembling theory into practice. From the beginning, McClellan was at odds with Lincoln on how to prosecute the campaign. Although Richmond may have been the desired target of both the president and McClellan, there was little beyond that on which they agreed. The theater of war had been selected (Jomini’s first point of strategy), but McClellan seemed incapable of identifying the decisive points favorable to his operations (point 2). The general’s selected zone of operations could scarcely have been worse: when his forces approached Norfolk, he learned that the city had emptied and the river forsaken, which offered the ability to close on Richmond via the river instead of crossing over the swamplands of the Chickahominy.[18] Bafflingly, McClellan refused, and this may have contributed to the inability of Union forces to take Richmond since the Navy was not able to coordinate their attack with McCleallan’s ground forces. McClellan’s failures as wartime commander, brilliant in academics and planning but ineffective on the battlefield, did little to advance a competent Northern strategy, Jominian or otherwise.

[1] Antoine Jomini, The Art of War, trans. H. Mendell and W. P. Craighill (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1879), 23.

[2] Carol Reardon, With a Sword in One Hand and Jomini in the Other : The Problem of Military Thought in the Civil War North, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 19.

[3] “Flanking,” The Soldiers’ Journal (Richmond, VA), 22 June 1864.

[4] George W. Brown and Thomas H. Hicks to Abraham Lincoln, Thursday, April 18, 1861, The Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[5] Lincoln To Thomas H. Hicks and George W. Brown, April 20. 1861, Collection IV.

[6] Abraham Lincoln to Simon B. Buckner, Wednesday, July 10, 1861 (Kentucky Neutrality), The Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[7] Abraham Lincoln to Beriah Magoffin, Saturday, August 24, 1861 (Reply to Magoffin’s letter of August 19), The Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

[8] Carol Reardon, With a Sword, 22.

[9] Ibid, 24.

[10] William C.C Davis, Battle at Bull Run: A History of the First Major Campaign of the Civil War (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 73-74.

[11] Henry J. Hunt, Report of Light Battery M, Second Artillery, U.S.A., under command of Major Henry J. Hunt : Battle of Bull Run, July 21st, 1861 [Washington, D.C.?], [1861], 2.

[12] John M. Palmer to Lyman Trumbull, Wednesday, July 24, 1861 (Situation in Missouri; Endorsed by Abraham Lincoln, July 31, 1861). Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress.

[13] Carol Reardon, With a Sword, 27.

[14] Ethan S. Rafuse, “McClellan and Halleck at War: The Struggle for Control of the Union War Effort in the West,

November 1861-March 1862,” Civil War History, Vol. 49 Issue 1 (March 2003): 34.

[15] Major General Magruder’s Report on the Operations on the Peninsula, 1862, 5.

[16] James Ford Rhodes, “The First Six Weeks of McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Apr 1896): 466.

[17] Ibid, 470-471.

[18] Ibid, 468.

thanks for sharing important history

LikeLike

I appreciate that! And thank you, as well. I’ve watched a couple of your videos. Very interesting topics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you pal no worries have a great and groovy day

LikeLike